There are numerous by-products, of some process or industry, that are considered waste and and it only takes a little imagination to recycle them to be of use for building and construction.

Flyash

As a fine residue from coal-fired thermal power plants, flyash is a serious health hazard if released into the atmosphere. These days, it is filtered out before the flue gasses are released and then dumped in “ponds”. But what’s to be done with all this flyash? For one thing, we can make good use of it!

Flyash is a pozzolan — it has cementatious properties. While it can’t be used as an alternative to cement, it can act as a good filler for concrete which turns out stronger – and uses less water – than that made with cement alone.

In India, it is usually used to manufacture bricks that are stronger than the traditional terracotta ones; they use less mortar to lay, absorb less water and don’t require to be fired in a kiln, thereby not adding to the pollution in the atmosphere.

For the [RaBV] Bungalow in Karjat, we used flyash bricks and adding red iron-oxide to the mix. The resultant colour was a pale terracotta that is quite pleasant. Next time, I’ll try getting yellow bricks with yellow oxide. The manufacturer’s factory is near Virar, North Bombay (Mumbai), but the quality of the last batch of bricks we received deters me from recommending him.

Bagasse

This is the waste from sugar cane once the sugar is extracted. It can be used to make particle boards or other fibre-boards. Unlike wood-based products, it isn’t affected by borers. One company, that I know of, which uses agricultural waste products like cotton stalks or bagasse is Ecoboard Industries based in Pune.

Rubber Wood

Rubber wood is a by-product of rubber plantations that are found over a large part of Southern India. Left to itself, the wood rapidly deteriorates and discolours but, if treated properly, can be used for a variety of purposes – especially in furniture. It has a pale golden yellow colour when given a natural polish. One drawback that needs to be taken into account is the extent of its response to moisture. Since the wood is kiln dried, the moisture content is low when you receive the material but it can react quite alarmingly during the monsoon.

Rubber wood can be got from any of the producers listed here

Coconut Plyboard

This is a product that, I have to admit, I haven’t used. ! I’ve seen the samples however and what’s so appealing about it – apart from the fact that it’s made from waste coconut husk – is the wonderful dark natural colour.

The company that manufacturers it, Natura Fibretech Pvt. Ltd, is in Bangalore, so getting a small quantity to Bombay works out much too expensive.

Construction Debris

This is not something that can be used on a regular basis or in large quantities but, when one is doing a plinth backfill, it makes sense to use debris from some other construction. Every little bit helps. The tragedy of places like Bombay is that this debris is being systematically dumped by unscrupulous builders into our vanishing mangroves.

More

If you are the manufacturer/dealer of any product that you feel is appropriate for this page, please fill this form stating clearly what exactly makes your product green/sustainable.

Please note that Greenwashing will not get you anywhere and inclusion of the product is not guaranteed and is entirely at our discretion.

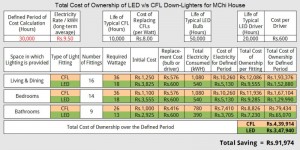

For the MChi interior site in Bombay (Mumbai), I found some really nice LED light fittings but they are more than three times the cost of identical CFL fittings. Now we all know that LEDs consume very little electricity and they have an extremely long life but I wanted hard numbers to convince my clients – after all, they are the ones paying for everything.

For the MChi interior site in Bombay (Mumbai), I found some really nice LED light fittings but they are more than three times the cost of identical CFL fittings. Now we all know that LEDs consume very little electricity and they have an extremely long life but I wanted hard numbers to convince my clients – after all, they are the ones paying for everything.

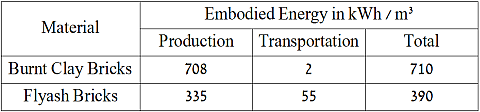

So, as you can see, there are no hard and fast rules when it comes to distance. Each case has to be looked at individually and assessed on merit. We also don’t always have ideal situations but we must, at the very least, aim to minimise the embodied energy of our structures.

So, as you can see, there are no hard and fast rules when it comes to distance. Each case has to be looked at individually and assessed on merit. We also don’t always have ideal situations but we must, at the very least, aim to minimise the embodied energy of our structures.

Decades of neglect had made a shambles of this wonderful building from the 1880s. When a survey was conducted, it was found that, the area to be renovated was a long-enclosed verandah. In fact, every single tenant of this heritage building had converted their deep verandahs into cabins.

Decades of neglect had made a shambles of this wonderful building from the 1880s. When a survey was conducted, it was found that, the area to be renovated was a long-enclosed verandah. In fact, every single tenant of this heritage building had converted their deep verandahs into cabins. A dynamic young trio wanted to go it along in the ad-film industry so their impact had to be much bigger than their budget.

A dynamic young trio wanted to go it along in the ad-film industry so their impact had to be much bigger than their budget.