Entrance aangan to a cottage. The overall design was meant to create the ambiance of an Indian village.

Satya Health Farm, now Satya Resort, is situated in the Karjat region — about two hour’s drive from Bombay. With the river Pej flowing past the northern edge of this 50 acre (20 Hectare) property and surrounded by the ranges of Matheran, Dhak and Bhimashankar, it is an excellent spot for either purpose.

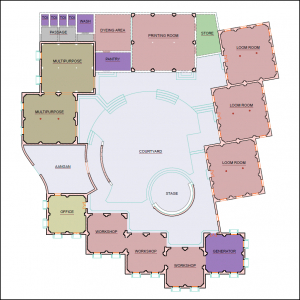

The brief given by the developers was to recreate an Indian village. Not in the literal sense of course – Indian villages are generally short of water, electricity and telecommunication infrastructure. What the clients really wanted was, for the design to generate a feeling of rustic community. A place where time flows slowly and you are not under any kind of stress. No deadlines, no schedules — just a feeling of well-being.

Some of the rooms are in arranged around central open-to-sky courts

The layout makes full use of the variable slopes with clusters of ground-hugging cottages following the contours of the site. A monsoon stream flows through before joining the river to the north. The river itself is a perennial one since it comes from the Bhivpuri Power Station which generates electricity throughout the year.

The requirement for peace and tranquility is reflected in the choice of building materials and the overall aesthetic appearance. Rooms are arranged around courtyards or as part of a larger cluster – a Mohalla. With their front Aangans and rear Otlas every room gets as much space outside, as within. The idea is to draw people out – to cajole them into shedding the attitude that makes city folk hesitate to speak with their neighbours.

The cottages are built very close to each other without sacrificing privacy.

Locally made burnt bricks were used to erect a load-bearing structure resting on a foundation of local black (basalt) stone. This is topped by a traditional wooden roof with Mangalore tiles. The entire roof planking was done with treated rubber wood which is not just economical but ecologically friendly too, being a by-product of the rubber industry.

The design needed to have a feeling of softness. This was achieved by avoiding sharp edges and by the use of warm colours on the walls. The flooring too, is of red terrazzo tiles with patterns and borders in green and yellow marble. For the detailing, traditional forms and patterns have been drawn upon – in the archways connecting cottages for example.

The lighting, especially for the exteriors, has been deliberately kept at low levels not just because bright lights would attract insects from miles around but also because harsh illumination would shatter the tranquillity and obliterate much of the night sky.

You may also want look at the list of materials, consultants and contractors.