Challenging a Mindset

I have often found that builders, architects and indeed, clients, want to make even the smallest structures using reinforced concrete cement – or RCC. This is a mixture of cement, sand and aggregate (stone chips of gravel) that is cast around a framework of reinforcing steel rods. Once the skeletal framework of concrete beams and columns is in place, the gaps are filled in with bricks for the walls. But bricks are perfectly capable of taking the load of low-rise structures by themselves so, why have the RCC at all?

Unfortunately, many people have become obsessed with using RCC because it holds the promise of a more stable construction – a notion that is not often true. To be sure, if you’re talking about a multi-storey building, RCC is the cheapest way to go. But if you’re making just a one or two storey house, load-bearing bricks will do just fine. To illustrate, at the time of writing this, I’m living in a four storey load-bearing building that was constructed in c.1900. It’s obviously seen earthquakes, storms and floods and doesn’t seem the worse for the wear. In contrast, other buildings in my neighbourhood – those built using RCC – seem to need extensive repairs every 7-10 years.

Slipshod Work

Even discounting the cement-shortage years of the 1970s, concrete structures in our country are, by and large, badly made. In our climate, the steel often starts to rust even

before the casting begins and, the concrete cover is not enough to protect it from further corrosion in humid areas. Worst of all, the columns and beams are, more often than not, found to be honeycombed once the formwork is removed (this is quickly patched up but the structure remains inherently weak).

Finally, there is a widespread consensus among both, literate contractors and illiterate workers that chiselling away some concrete to embed, say, electrical conduits is perfectly allright as long as nothing collapses in the next twenty four hours. Others who consider themselves very safety concious will make sure they don’t actually cut the steel in their endeavours. This would be very funny if it wasn’t so dangerous.

Unfriendly to Nature

Apart from all this, by its very composition, RCC is a wasteful material. It uses large amounts of cement which, in turn, require huge amounts of fossil fuel to produce. The structure becomes heavy and, a fair portion of its cross-section goes in supporting its own weight. Finally, once the life of the building is over, it is almost impossible to extract the steel (also an energy-intensive material) for any meaningful purpose.

Reducing the Ecological Impact

There are many ways in which RCC can be made less wasteful — using filler slabs, for instance. But doing that requires a little extra effort and there is a general apathy that prevents even this simple method from being used. I once had the opportunity to climb onto a 100-year old lime-concrete vaulted roof that was undergoing repair. I was amazed to see how the builders had used ordinary terracotta pots to lighten the structure.

Another alternative which can be used for select elements is ferrocement or ferrocrete. This uses thinner sections with minimal steel – often just chicken mesh – but relies on the element’s geometry to provide structural stability. For example a roof slab can be folded like a paper fan or, a staircase which is an ideal candidate for ferrocement will use less than 25% of the material compared to a traditional concrete one. Not many contractors know how to do it correctly though, which leads them to avoid taking up such work. That, in turn, makes it a rare thing which makes everybody very hesitant. It’s a vicious cycle.

And of course, the easiest way to avoid concrete is in low-rise structures which usually don’t require it in the first place.

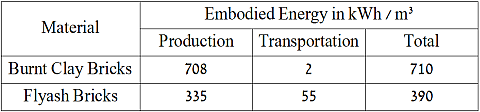

So, as you can see, there are no hard and fast rules when it comes to distance. Each case has to be looked at individually and assessed on merit. We also don’t always have ideal situations but we must, at the very least, aim to minimise the embodied energy of our structures.

So, as you can see, there are no hard and fast rules when it comes to distance. Each case has to be looked at individually and assessed on merit. We also don’t always have ideal situations but we must, at the very least, aim to minimise the embodied energy of our structures.