Tread Lightly on the Land

In my experience developers, who are trying to sell multiple plots of land, often spend huge amounts of money completely flattening everything in sight. We are then left with a veritable desert because he has also chopped ever tree, ripped out every bush and completely eliminated the ground cover – not to mention mixed the fertile topsoil with the useless layer underneath. Worst of all, he has managed to completely destroy the natural drainage patterns of the entire development and many others downstream as well.

It is not correct to blame the developer alone for such a situation. He is doing this because he believes that unless he provides a completely level a plot, it will never sell. The demand for levelled land often comes from the clients and, in some cases, their architects. So unless the promoter of the project is already enlightened on the environmental fallout of such indiscriminate levelling (or if he is somehow made aware before the bulldozers move in) this is a very common scenario.

It doesn’t have to be this way and there are a number of things we can do to preserve the ecology of a given site.

Preserve Topsoil

Topsoil is the uppermost layer of the earth – just a few fragile inches of organically rich soil that allows the growth of plants. On average, it is said that a single inch of topsoil takes a century to be created. This, then, makes it imperative that we do all we can to preserve and protect it. Almost always, during construction activity it is lost and, once the building is built, new topsoil has to be imported from somewhere else thereby making some other land infertile.

Pretty senseless, isn’t it?

Now it is a labour-intensive process to take off a layer of topsoil and store it for the duration of construction but it is by no means difficult. All it needs is for the clients to be willing to pay a tiny fraction extra of the total project cost even if the average contractor thinks they’re loony.

The topsoil can be piled in a corner of the site (or stored in bags) where is doesn’t come in anyone’s way and then spread out where required when the landscaping is to be done.

Keep the Existing Vegetation

Every piece of land has a certain character that makes it what it is. Unless you’re buying a plot in a development where everything has already been killed, this character are probably what attracted you to that particular piece of land in the first place. So then why do we not preserve the vegetation as much as possible. Sure, we’re sometimes faced with impossible situations and have to cut a tree or some bushes. In such cases, we should replant at least three times the number to compensate.

More often than not, we can save trees that are “in the way” and actually make them an important part of the design. This needs for the architect to be creative and, equally importantly, for the contractor and his team to be sensitised to such a requirement. From experience I have found that a contractor, labourer or even a truck driver delivering material to the site considers them to be obstacles that must be gotten rid of because they hinder the free flow of materials and labour. Contractors must therefore be made aware before the work starts that you are very keen on protecting such vegetation. If you think you can safely tell them at some “appropriate time”, it will probably be too late.

Maintain Drainage Patterns

A plot of land doesn’t exist in isolation. It is merely a small part of a large jigsaw puzzle that covers the entire earth. In non-urban settings, especially in areas of high rainfall, any water that passes through your land eventually goes to someone else’s. If we change that and either block the water’s entry into the site (or exit from it) we are interfering with the overall system.

While it is true that even natural drainage patterns often change on their own, they do so only when there is an alternative. Suddenly blocking the natural flow of water is either foolhardy (if you’re trying to keep every drop out) or selfish (if you’re trying to keep every drop to yourself).

Again, sometimes we have to modify a watercourse but it should be done in such a way as to not affect the people who live downstream. For example, there was a site in Zirad, Alibaug, where the entire plot, especially the part where the house was to be built, would be flooded during most of the monsoon making it potentially impossible for the clients to enter or leave the house during those months. Their early attempts to make a straight stone dam at the point where it entered the site came a cropper when the first rains washed it away. Surprisingly, this dam had been suggested by the local villagers – which leads me to believe that they’ve been living off the sale of land (instead of what they produced from it) for far too long.

While there is no static rule for dealing with storm drainage the attempt should be two-fold:

- Try and preserve the entry and exit points for water to and from your site

- Allow the water to flood gracefully. Trying to restrict it too much will invite trouble at some stage. The massive flooding in Bombay (Mumbai) in July 2005 was a result of the Mithi river being constricted to such an extent that, by the time it broke its embankments, it had swollen to unnatural levels.

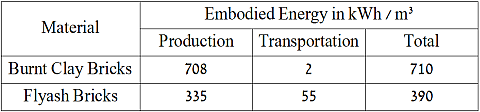

So, as you can see, there are no hard and fast rules when it comes to distance. Each case has to be looked at individually and assessed on merit. We also don’t always have ideal situations but we must, at the very least, aim to minimise the embodied energy of our structures.

So, as you can see, there are no hard and fast rules when it comes to distance. Each case has to be looked at individually and assessed on merit. We also don’t always have ideal situations but we must, at the very least, aim to minimise the embodied energy of our structures.