The design of a private residence at Kondhwa, Pune, was a very exciting project. No Reinforced Concrete Cement (RCC) has been used and we opted for load-bearing walls that are cheaper and, in my opinion, better for a building of this type.

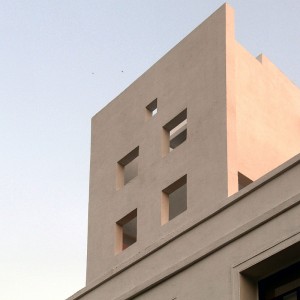

Kondhwa has grown rapidly & haphazardly since the ‘90s. The skyline c. 2005

The exciting part included waste water recycling, rain harvesting and setting up solar panels – at least to heat the water – photovoltaic energy is still too expensive to be justifiable in areas that are connected to a power grid.

Kondhwa is an area that’s growing more rapidly and haphazardly than many other parts of Pune. What used to be rolling hills where nomadic grazers brought their sheep as little as 10 years ago, is now largely denuded and taken over by builders. In such a scenario, where new highrises and swanky malls are coming up each day, a bungalows-only development – that too on a hilltop – is refreshing indeed.

A vastu puja was done before the clients moved into the home

The client contacted me though this website and, after some informal discussion via email, we found that our views on many things including materials and water harvesting were very similar. There was one condition, however – the house had to pass muster on the vastu front as well. I made it clear that despite my writeup on the subject, I was absolutely not an expert on vastu and somebody else would have to give the specifications before designing commenced.

As it turned out, that was no problem at all. The expert that the client consulted gave her views beforehand and they matched, to a large extent, my reading of climate-related factors.

Design Principles

View of the house from the approach road

Ideally, anyone would think we should have large openings for maximum natural light and ventilation. The problem is, with Pune’s hot and dry climate, this isn’t such a good idea after all. In a coastal area like Bombay, even in the hottest months, as long as the air circulates, you can get by. Pune, though, is far removed from the sea and the temperatures are, consequently, more extreme. In summer, a hot breeze blows across from the South and, in such a place, you’d want to insulate the structure instead of open it out.

View of the house during construction. The ladi-coba method was used for flooring and brick arches spanned the openings to the courtyard

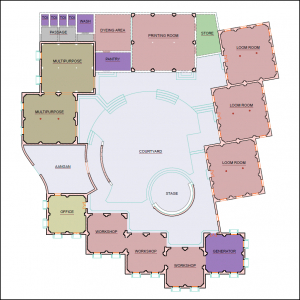

Having said that, it is imperative not to totally stifle all movement of air and so a central atrium (brahmasthan in the vastu shastras) was designed to set up a slow, comfortable, convection that works in all seasons. This was combined with standard sized windows and deep overhangs to prevent the entry of heat during the summer months.

Sun studies were also conducted to see how much direct light would penetrate at different times of the year. Unfortunately, the data on wind in the area is scanty but whenever I visited the site over the next few months, the wind direction was, unexpectedly, from the North-East. Local people also mentioned that the area receives lashing rain, so that bit of information had a direct impact on the awning design.

Materials

The foundations and plinth walls were made of local basalt. The outer layer of stone was shaped by hand -- a rather labour-intensive process

As far as possible, locally available materials were used in this construction. The foundation, for instance is of black basalt which is abundant throughout the Deccan. To minimise wastage, it was only being partially dressed and the natural randomness of shape was preserved to the maximum. The plinth itself was filled with broken rubble from a recently demolished structure.

Being just a ground + 1 structure, the walls are load-bearing and the first slab has the traditional “Ladi coba” system except that, instead of teak, [Tectona grandis] like it was in the old days, we’ve decided on rolled steel sections that can easily be reused at the end of the building’s lifecycle. The only RCC used was for pre-cast lintels over the doors and windows.

Bullocks working on the ghani — a circular pit with a 1 ton grinding stone where the lime & sand are mixed with water and pulverised together. The mortar that results is mixed with jaggery which helps it to set.

Another interesting and unusual thing about this house is that it was built with lime mortar. It may sound odd and, although lime is not as “standardised” a material as cement, the end construction is often more sound. Additionally, unlike cement lime mortar uses little or no fossil fuel to manufacture and, hence, is much more environmentally sound. It does add to the work-load of the contractors though and it is difficult to get workers who are still familiar with this material.

Solar hot-water panels

That’s not all, though. Brickwork set in Lime has the advantage of not cracking easily. Lime plaster, especially when finished with lime wash, has the property of “self-healing” any cracks because, the free lime carbonifies and merges with the plaster.

Other Nature-friendly Systems

Energy Saving

- CFL, energy-saving compact fluorescent lights

- Natural light and ventilation (to a large extent from the courtyard)

- Heating of bath/kitchen water using roof-top solar panels

Water Saving

- Low-flow dual-flush cisterns for WCs

- Filtering grey water from baths for flushing and kitchen water for gardening

- Recharging ground water by harvesting rain

Waste Management

- Dry garbage (paper, plastics, glass and metal) is segregated and given to the kabbadiwala

- Raw sewage is treated organically and the only discharge is clean water that is put back into the ground.

Decades of neglect had made a shambles of this wonderful building from the 1880s. When a survey was conducted, it was found that, the area to be renovated was a long-enclosed verandah. In fact, every single tenant of this heritage building had converted their deep verandahs into cabins.

Decades of neglect had made a shambles of this wonderful building from the 1880s. When a survey was conducted, it was found that, the area to be renovated was a long-enclosed verandah. In fact, every single tenant of this heritage building had converted their deep verandahs into cabins. A dynamic young trio wanted to go it along in the ad-film industry so their impact had to be much bigger than their budget.

A dynamic young trio wanted to go it along in the ad-film industry so their impact had to be much bigger than their budget.