Many people dream of leaving the city to lead a slower, more meaningful life outside it. Few, however, are able to live that dream. Just a stone’s throw from the [RaBV] bungalow here is a sustainable weekday home of a couple who come into the city on weekends.

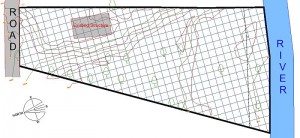

Site Conditions

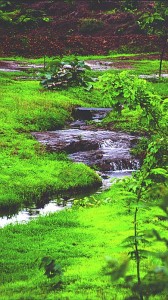

Much of this one-acre site is between 1.5 and 3m above the average water level of River Pej, so during the monsoon, the lower section of the plot is often flooded once or twice for a few hours at a time. The initial plan was to build almost touching the river but that would mean building on stilts. Instead—taking into consideration the high water mark of 2005 which saw the worst flood in living memory—we decided to build on a small rise at the other end of the plot. Thanks to climate change, such freak events as the cloudburst of 26th July 2005 are likely to happen with increasing frequency and we must understand and prepare for them instead of brushing these facts under the carpet.

The little rise is next to the access road so the approach to the car parking area is a little steep but, other than that, there are no disadvantages. There used to be a shed on this mound so there were no trees that needed to be designed around.

As the building is on a slope, the extra height at the bottom has been used to create two basements. One stores gardening and filtration equipment along with the rainwater harvesting tanks while the other has batteries, inverters and other electrical equipment for the photovoltaic solar panels.

Design Considerations for Sustainability

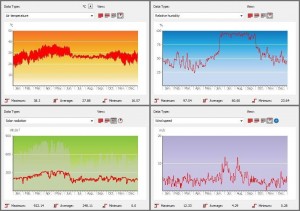

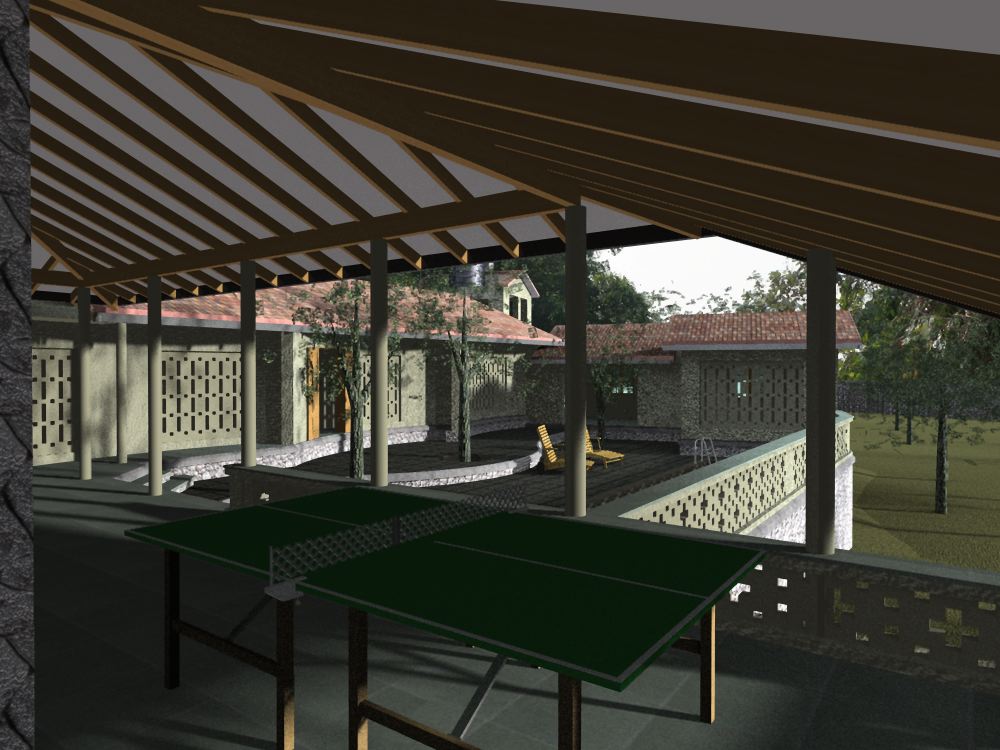

As with the [RaBV] bungalow, the climatic conditions to be considered were hot days and pleasant nights with a strong monsoon. We needed sufficient shade on the South and West sides and this was taken care of with deep verandahs. Air circulation and cross-ventilation were important to eliminate the build-up of hot air. For the most part, roofs are sloping with only a small fraction of flat terrace where the solar hot-water systems are placed.

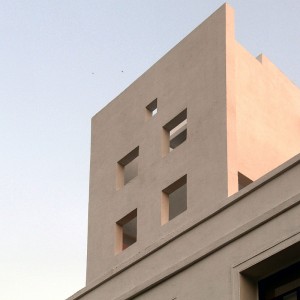

Instead of a typical compact layout, this house was designed as a series of spaces with clear zoning of public and private. When seen from a distance–and a height–it looks like three houses in a cluster rather than just one. Central to all three spaces is the court and the open tank. This is not some amoeboid pool for people to float around with a cold beer but a straight 15m strip for exercise. Oh, and it’s a tank because, well, it’s a tank. Water from here goes to the vegetable garden and to many of the trees on this plot.

The clients, currently in their early 50s, want to spend the bulk of their time here exploring their creative side. Accordingly, one of the major spaces in the house is a workshop to be used for painting, stained-glass making and sliver-smiting. There is also a small study, two bedrooms, a utility room, a living/dining room and a very large kitchen.

Materials & Systems

The foundations were constructed from local basalt and the superstructure from local bricks.We discussed the possibility of using fly-ash bricks but the clients had reservations because of the debate over fly-ash being carcinogenic.

Many internal walls were left un-plastered and the roofs had a steel structure with Mangalore tiles on battens without any under-layer.

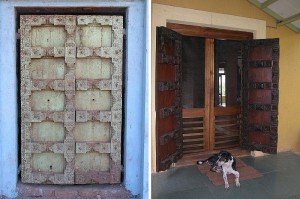

Doors and windows were either beautiful old ones that were salvaged from demolished homes or were made anew from reclaimed old Burma teak. The credit for sourcing them all goes completely to the clients. They also purchased five lovely old wooden pillars during their travels, which were incorporated into the design. Since these were only 2.5m tall, we made a tapered concrete base which was then clad with the same grey granite as was used for the adjoining parapet walls.

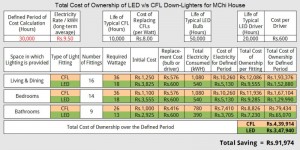

Energy

All the lights are low-energy, mostly LEDs, while the fans and refrigerator are inverter-type so their energy consumption is also lower than average. As these fans are a relatively new product, it remains to be seen if they stand the test of time.

Bath and kitchen water is heated using one solar panel on each of the terraces. There are also twelve photovoltaic solar panels on the roof of the workshop which provide enough electricity to run all the lights and fans as well as some of the appliances.

Water

A good amount of the rainwater is harvested. Some of it is collected in tanks for drinking water throughout the year. This is necessary as the river, though perennial, sometimes contains urea washed in from fields upstream; even though the water is clean enough for bathing and washing, it is not advisable to use it for drinking or cooking. The remaining harvested rainwater is used for recharging a bore-well that is an emergency backup water-source. Whatever rainwater is not harvested either seeps into the ground or flows directly into the river.

Embedded dual cisterns flush the low-flow WCs and kitchen waste water is sent directly into a soak-pit from where it percolates into the ground.

|

|

|

|

Project Participants

| Consultants | |

| Structural & Waterproofing | Mr. Ratnakar Chaudhari |

| Contractors | |

| Overall | Civil, Plumbing, Roofing, Painting | Mr. Rajesh Phatak |

| Electrical | Mr. Rafeek Shaikh |

| Carpentry & Joinery | Mr. Ramashankar Mistri |

| Specialised Agencies | |

| Solar Hot Water | Solar World |

| Solar Photovoltaic | Panels, Batteries, Inverters | Sunlit Future |

| Swimming Tank Filtration | Oceanic Enviro Pvt. Ltd. |

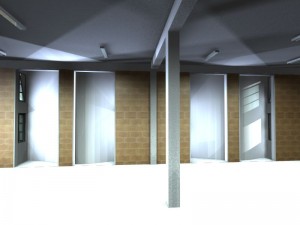

Decades of neglect had made a shambles of this wonderful building from the 1880s. When a survey was conducted, it was found that, the area to be renovated was a long-enclosed verandah. In fact, every single tenant of this heritage building had converted their deep verandahs into cabins.

Decades of neglect had made a shambles of this wonderful building from the 1880s. When a survey was conducted, it was found that, the area to be renovated was a long-enclosed verandah. In fact, every single tenant of this heritage building had converted their deep verandahs into cabins. A dynamic young trio wanted to go it along in the ad-film industry so their impact had to be much bigger than their budget.

A dynamic young trio wanted to go it along in the ad-film industry so their impact had to be much bigger than their budget.